F These Brands: Rini

- Anthony Najm, Kayley Williams, Brea Cannady

- Dec 4, 2025

- 4 min read

Skincare is now being sold to children as young as three. Let that sink in.

Actress Shay Mitchell, best known for Pretty Little Liars, recently launched Rini, a skincare line for kids. The campaign shows toddlers in sheet masks at birthday parties, sleepovers, and play dates. The products are framed as a part of developing “healthy habits”. But the brand, which claims to be gentle, fun and safe, follows a familiar industry playbook: manufacture insecurity then monetise it. It does this by teaching parents that normal toddler skin needs “care” and routines, so children start to see their faces as something to work on, not just live in.

The core truth is simple: toddlers do not need skincare. Their skin is already healthy. Encouraging kids to mask, hydrate and care for their faces at such a young age embeds adult beauty standards before children even have a chance to form their own self image.

Tiny Consumers, Big Implications: Why Skincare for Kids Is Not a Neutral Idea

When an adult applies a sheet mask, it is framed as self care. When a toddler does it, the meaning becomes something different. Instead of imagination, storytelling or messy creativity, the child is encouraged to focus on their appearance instead of what the child can create or explore. It turns skincare into a child’s first ‘routine’, teaching them their skin needs attention from the moment they can walk.

This is the shift that needs attention. Sheet masks stop being "just a product'" - they become a teaching tool for the beauty industry. Once children learn that looking good is part of play, the foundation for future body image problems is already in place. The message sinks in before they can question it.

The Advertising Standards Authority warns that children are uniquely vulnerable to media and advertising messages. They lack the critical skills to challenge what they see. Beauty marketing that frames natural skin as something to fix fuels early anxiety, body dissatisfaction and internalised pressures that shape self esteem before children have developed their own identities. And the industry knows there is money in it. Vulnerability becomes a commodity. Statista projects the Baby and Child Skincare market will reach £461 million by 2029, driven by brands inventing problems and selling children the solutions.

Rini turns a basic childhood setting into a beauty environment. The birthday party scenes, the mirror moments, the group activities. It all positions skincare as something children should integrate into daily life. And because everything is cute and animal themed, it looks safe. But it teaches that the face is something to manage, perfect or fix. Children absorb that message long before they are ready to understand it. This is not self care. It is appearance conditioning.

The Celebrity Effect Makes It Even More Powerful

The fact that Rini is celebrity backed accelerates the harm. Celebrity branding makes parents assume the products are safe and positions the routine as aspirational for kids. That trust is powerful. It turns a harmful idea into something socially acceptable overnight, not because it is healthy or appropriate but because it carries a familiar face. This is how beauty norms move into early childhood without resistance.

Shay Mitchell has said that Rini was inspired by her daughters wanting to do what mommy does during her skincare routine. This is not a criticism of anyone's parenting. The concern is that people with high level of influence (both celebrities and parents) are endorsing products that can shape children’s perceptions of themselves at such a formative age.

Celebrities carry credibility by default. With that comes a responsibility to consider how promoting products might affect young audiences and their internalised beauty standards. It gives an impression of legitimacy and care while pushing appearance expectations onto an age group that does not need them. This is not accidental. It is a calculated use of influence to expand the beauty market.

There is no ethical justification for this. None.

The Psychological Cost We Keep Ignoring

Introducing appearance routines this early is linked to long term body image issues. Research shows that early appearance awareness increases self comparison, heightens pressure to conform and makes children more vulnerable to low self esteem later in life.

Rini frames its products as tools for confidence. In reality, it teaches that confidence comes from fixing or managing the face. It links wellbeing to appearance before children fully understand what wellbeing means. That is the real damage, not the masks or the packaging. The damage is the idea that a child’s face needs improvement in the first place.

Parents are not to blame here; the industry is. Most people do not have the background knowledge to question a cute, colourful brand that uses words like confidence and emotional wellbeing. Brainwashing stretches back across several generations. Most people have no reason to know the psychological risks this kind of messaging creates; that is why companies get away with it. There is no major cultural pushback yet. This is relatively new territory, and without strong public awareness, brands are free to shape the narrative however they want.

Why Rini Belongs on the F These Brands List

Rini is a sign of how far the beauty industry is willing to go to secure its next generation of consumers. There is no ethical way to market skincare to toddlers. Any campaign aimed at very young children and their parents turns normal skin into a problem and beauty routines into a childhood expectation.

Rini pushes skincare into early childhood with no real concern for developmental needs or psychological impact. It treats beauty norms as something that should start in preschool, shrinking childhood and raising appearance anxiety long before children even reach primary school. This is not a future we should accept as inevitable.

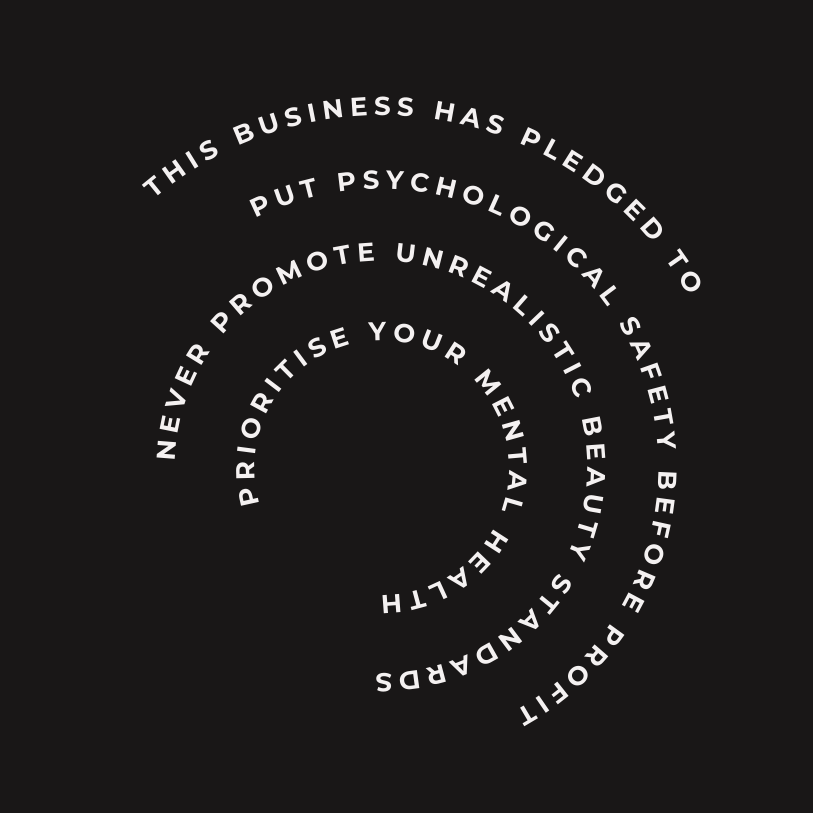

If you refuse to watch the beauty industry target kids, add your name to the Index:MH pledge.